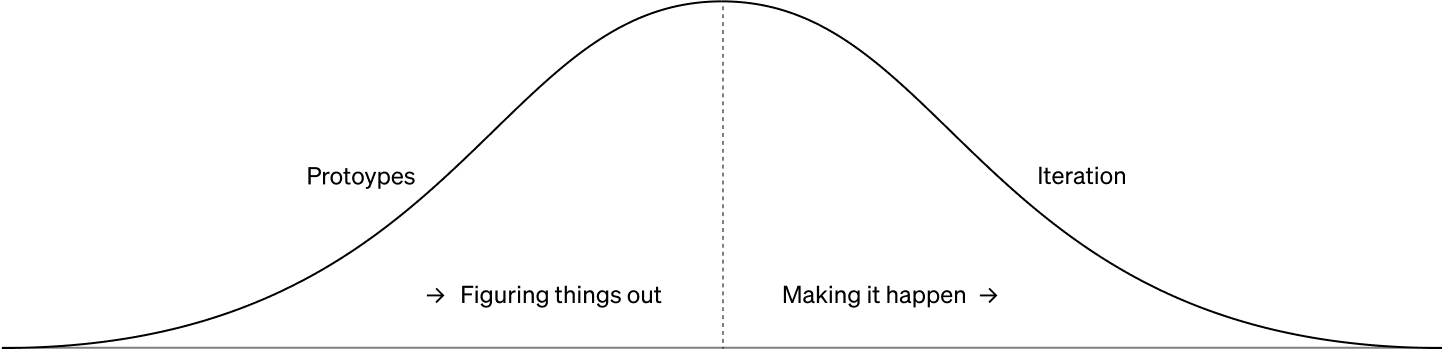

When building software products, we often hear two separate phrases with different meanings used interchangeably: iteration and prototyping. They're not the same thing, but they're related over time during a build process. The easiest way to see the difference is to map them on a Hill Chart.

Prototyping comes first, at the start of the hill. We're trying to find the best method of solving for a particular intention within the project and use that as a tool to make better decisions. For example, do we show an onboarding flow as multiple choice radio buttons or do we rephrase the questions as yes/no and use a swipe left/right flow? If it's the later, how responsive to touch will it be on a smartphone?

Iteration happens after the apex, when we've "walked up hill" to discover all the interrelated dependencies so that we're able to decide exactly how we're building the thing. Iteration is the descent along a singular path towards a release. No new requirements should be introduced. Instead, like any editing process, we're probably shedding them as we nail down the existing details and make them work.*

During a build process, we always hope not to discover anything that puts the project at risk. And that is the job of prototyping: discover technical or design possibilities and determine if they're opportunities or trade-offs. If there is some essential discovery that puts the project at risk, we want it to occur during protoyping, if at all. But we would not want nor expect that during any iteration work. That would be a sign of not enough initial prototyping or even insufficient research prior to signing-off the build process.

It's important to note that any project build phase should be aiming to release as soon as possible. Deferring features for later releases is the easiest way to stick to the timeline. This means we can also think of iteration via projects, not just within a project.

We can now generalise these methods together as specific tempo-based jobs: Prototype to discover. Iterate to release.

Prototyping does not mean "design tools"

Don't make the mistake of thinking that because Figma has a "prototyping" mode that its your prototyping tool. You may want figure out how far you can get with the Google Sheet API before you add a database, and you can't do that with any design tool.

And if it is a design hypothesis (of the visual, flow or interaction kind) that you want to test, then designing in code is as close as possible to "the nitty-gritty material of the medium" you can possibly get. As I've said before, what often looks perfect in Figma can look not at all perfect in the reality of the browser. Inspect your assumptions in the DOM.

Developing a spidey sense for discover-or-release

While these two concepts are not the only two things that occur during a build phase, discover-or-release is a useful abstraction to distinguish between attitudes in decision making at different times during the process. Here's a few ways to think of them:

-

Prototyping is uphill. Iteration is downhill.

-

Prototyping discovers requirements. Iteration binds requirements.

-

Prototyping creates a flow of investment. Iteration creates durable stock.

-

Prototyping pulls towards complexity. Iteration pushes towards simplicity.

-

Prototyping diverges the possible. Iteration rounds the probable.

Which ever way you say it, the key question is: are we trying to discover ways to solve a problem or are we trying to release a solution?

This helps us—as a team—stay focused on doing the right thing at the right time to prevent unnecessary loss of momentum.

Simplicity on the far side of complexity

Simplicity is interrelationships that make it feel more like one thing. Complexity is interrelationships that make it feel like many different things. Ryan Singer

Alfred North Whitehead said "the only simplicity to be trusted is the simplicity on the far side of complexity." Simplicity is always the desired outcome for a software product because it represents a user experience that wins hearts ("delight") and minds ("don't make me think"). To get there—to make the thing whole for a person using it—the build process must traverse upwards through discovery to the fog of decisions before we can slash-and-burn, edit-and-cut, spit-and-polish downwards through the thicket of details.